Anyone who is not convinced of Iran’s aspirations to regional hegemony – or just expansion of power, if you prefer – should read Amir Taheri’s Wall Street Journal piece from Monday on that topic. Taheri has done American readers the service of collecting in a single piece a summary of Iranian activities to destabilize the US-friendly regimes in Morocco, Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, Kuwait, and Bahrain – the latter two of which host major Persian Gulf bases for American forces.

Revolutionary Iran has engaged in such activities at varying levels over the years in some of these nations (Lebanon, obviously, but Iran has sought to revolutionize Muslims in Morocco for some time as well, and undermine the Western-friendly monarchy there; and Tehran has long supported internal insurgents in Egypt also). But the last year has seen an unmistakable concatenation of Iranian efforts across all these Arab Muslim nations – efforts that appeared to surge in March 2009, with a sensational Iranian reference in a political speech to the Persian Gulf nation of Bahrain as “part of Iran.” Tehran has been working through militants in Bahrain, as it has in Egypt, where 68 were arrested in December 2008 (four identified as members of Iran’s paramilitary/terrorist Qods force), in what Egyptian leaders described, in their April announcement of the operation, as an Iran-backed plot.

Taheri’s summary recounts a multi-pronged effort to cultivate radicalism and undermine stable governments. It involves the use of commercial front companies (Egypt reports having identified 30 to date), charitable organizations, cultural centers, and Hizballah cells – or cells formed by sympathetic local radical groups. It shares similarities with the madrassa network financed and promoted by Saudi Arabia (and to a lesser extent, other Gulf oil sheikhdoms), but it is much more focused on immediate and active measures against host governments. The purpose of this campaign is, again, to destabilize Western-friendly regimes.

By itself this regional push constitutes confirmation of the methods Iran is likely to use to squeeze America and the West out of the Middle Eastern and North African region (see my February piece “Deterrence and the Superpower”). As columnist Caroline Glick points out, the US is doing nothing about these Iranian efforts today. Even with a change of national leadership, we may justly suspect that Iranian acquisition of nuclear weapons will be an effective deterrent to any glimmerings of reaction, and counter-push, on our part.

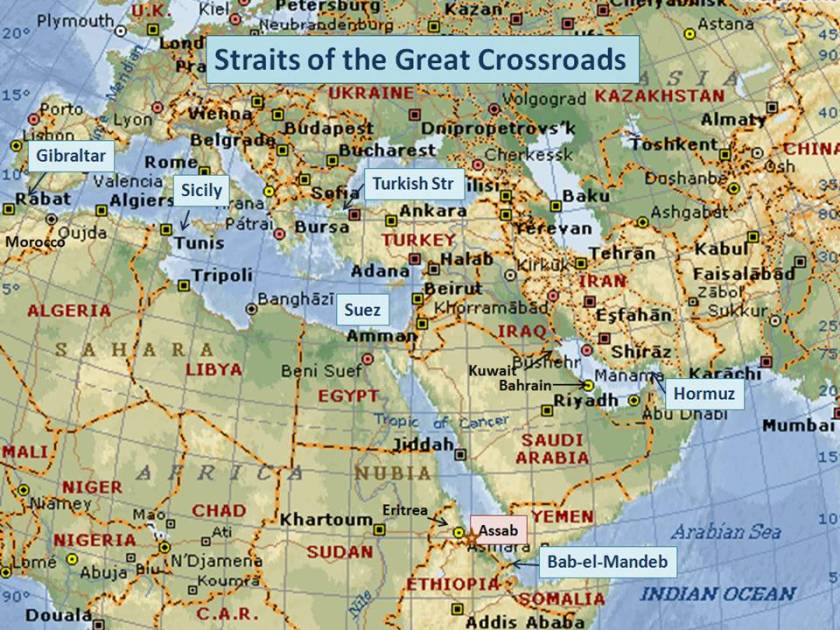

But Taheri’s summary also deepens the context in which to view Iranian actions in a corner of the region that is already unstable – a corner where Iran already has regional partners, and where the geographically-pivotal nation cannot effectively govern itself: the Horn of Africa. There is a recognizable pattern to Iran’s strategy, if we consider her activities in Eritrea, Somalia, Sudan, and the six nations listed by Taheri. From Morocco to Egypt to Somalia to Bahrain, they all represent geography vital to the maintenance of free, secure shipping in the region’s maritime chokepoints.

Morocco, of course, lies on the African side of the Strait of Gibraltar, the Western entrance to the Mediterranean Sea. Westerners have been accustomed to a quiescent Strait of Gibraltar for so long that we don’t even remember that it has been, in the past, a source of menace and vulnerability. The United States and Europe have considered a free, unthreatened Strait a core of NATO security for decades, but up through the end of WWII it had been fortified by some nations against others for centuries. Great Britain remained determined to hold her tiny slice of territory on Spain’s side of the Strait through the 1960s, when Gibraltarians voted on whether to remain part of Britain or revert to Spain (they voted in 1967 to stay with Britain, and are still a British territory). A tour of Spain’s Gibraltar coast, however, is also highlighted by gun emplacements facing Morocco, remnant not only of Spanish wars against European powers in the age of sail, but of the wars of Islam, and the Muslim invasion of Europe across the Strait more than 1200 years ago.

NATO, with Spain as a member, has maintained good relations with Morocco for decades. But it only takes menace on one side of a strait to make it inhospitable to shipping – unless it is held open by superior naval force. The problem with that, of course, is that there are three entry and exit points to the Mediterranean, and the need for superior naval force could be made to mount, very quickly, beyond the existing capabilities of NATO, by a concerted assault on the network of good relations and partnerships that now maintains maritime security through quiescence.

A friendly Morocco turned into a hostile one is just the beginning. Also on Iran’s list are Egypt and Jordan, flanking the Suez Canal, and Lebanon, relatively few miles north of it on the Levantine coast. Egypt has acted as a responsible custodian of the Canal for over four decades, guarding global interest in its fair and non-political operation – but as demonstrated in 1956 and 1967, a radicalized Egypt would be a very different quantity. The addition of a radicalized Jordan would place hostile, anti-Western powers on both sides of the northern Red Sea; and a Hizballah-ruled Lebanon would serve as a convenient alternate base for operations against commercial shipping going through the Suez chokepoint, as well as against Israel.

Bahrain, the small nation occupying a peninsula that juts into the central Persian Gulf, hosts the US Navy’s largest base between Crete, in the Mediterranean, and Guam in the South Pacific. The infrastructure there is vital to the naval operations that keep the Strait of Hormuz open. Their loss would not be recovered from quickly or easily; and a Bahrain under the policy direction of Iran would immediately become a base for coastal missiles and aircraft threatening commercial and naval shipping alike, in the Persian Gulf. Basing in Bahrain would allow Iran to menace shipping from both sides of the Gulf, and rapidly overtask Western naval forces trying to protect shipping in Gulf transit, and also hold the Strait open.

The nations with which Iran has already established militant ties on the Horn of Africa – Sudan, Eritrea, and Somalia – give Tehran the opportunity to complete the undermining of the US-guaranteed maritime free trade regime in the region, by menacing the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait. That this is precisely Iran’s intention is suggested by reports that cooperation agreements made with Eritrea last year include Eritrea’s cession of the port of Assab, in the southern Red Sea, to Iranian use as a base. Additional reporting, from Eritrean opposition groups but corroborated by NGOs, has indicated that Iran put troops in Assab in December 2008, and has stationed missiles of unspecified type there.

Some aspects of this reporting are unverified and suspect, in particular the claim that Iran transported troops to Assab via submarine. The sheer transit distance involved in such an operation would make it extremely challenging for Iran’s relatively inexperienced force of three Russian Kilo-class diesel-powered attack submarines (of which typically only two are combat-ready). It is not an impossibility, however – although transporting troops via submarine (particularly a comparatively small Kilo SS) would be exceptionally inefficient. If an Iranian submarine did disgorge troops in Eritrea in December, that would have been a performance for show, involving a very small number of actual troops (probably a dozen or fewer).

We may note, however, that the antipiracy effort in the Gulf of Aden, on the other side of the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, has given Iran – along with Russia and China – an excellent pretext for deploying naval ships to the region, outside of the leadership of the United States. (For my previous assessment of the disquieting aspects of that development, see “Not Your Father’s Cold War.”) Also worth noting is that Iran announced her first naval antipiracy patrol in December 2008. Reporting on potential port visits by Iranian warships in Eritrea is likely to be sketchy in the Western press, but such a development would make sense.

Iran’s continuing interest in Somalia – which includes being a major arms supplier of the Islamic Courts Union leader who now heads the UN-recognized Transitional Federal Government – portends obvious benefits to maritime chokepoint influence on the Horn of Africa. The endorsement of Western governments is virtually guaranteed to whoever can get Somalia organized ashore, and suppress the commercially-successful pirates who currently operate without let or hindrance by Mogadishu. Somalia also, however, forms the other side of a pincer created with Eritrea, around the Horn of Africa nation of Djibouti, where the US and France maintain small but increasingly significant military bases.

As Amir Taheri notes, this is what Iran is spending her revenues on: destabilizing governments, supporting terrorism and insurgency, and regional deployments of troops and weapons. Ironically, Iran’s European oil customers are paying Iran to attack Europe’s southern flank, and pursue control of a maritime belt without which Europe cannot even function as she does today. The US is not an oil customer of Iran, but we need not muse over selling the rope that will hang us, to recognize the threat Iran’s strategy poses to our national interests and our national security.

Forget oil: it is the hostile control of the waterways from the Strait of Gibraltar to the Gulf of Aden and the Strait of Hormuz that would pose a grave threat to global trade, to the geographic security of Europe, to the economic security of India and the Far East, and ultimately to our alliances in the Eastern hemisphere that make the great oceans a bastion for America, rather than a vulnerability. We have largely relied since the end of WWII on the quiescent security created by those alliances; and in spite of terrorism, that security regime is still vital, for both our allies and us. We maintain that security at low cost in military vigilance today: the Atlantic is not secure because we patrol it constantly or comprehensively, but because we secure it passively with alliances and partnerships on its other side. The same is true of the Pacific. Alliances are cost-effective and carry multiple benefits. Military patrols are a policy stopgap: tremendously expensive, and never able to close all gaps.

In attacking our alliances, directly or indirectly, Iran seeks to reshape the overall geographic situation. If Morocco and Egypt were radicalized and Western-hostile, for example, the pressure on Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya to follow suit would mount rapidly. The maritime security condition of the entire Mediterranean would change dramatically: where today shipping is essentially unmenaced there from any coast, it could, with surprising rapidity, be held at risk from the entire southern half of the sea. The highly interdictable central passage, the Strait of Sicily between Sicily and Tunisia, would revert to the vulnerability it experienced for centuries during the Barbary marauders’ regime – this time amplified by coastal missiles, paramilitary speedboats, shoulder-fired missiles, and night-vision goggles. Unsanctioned maritime traffic between Spain, Italy, and the African coast would be transformed quickly from a coast guard nuisance to a national security threat. Of course, from positions in northern Africa, much of continental Europe could be held at risk with ballistic missiles as well.

Could the US and Europe fight back and retake the territory needed to keep Europe and the Mediterranean secure? Yes – but it would be far more expensive and painful, and a far greater effort of will, than anything it would take to block and corral Iran today.

Moreover, Europe’s eastern front, and the third entry point to the Mediterranean – the Turkish Straits – will not remain in a static condition if Iran is allowed to push revolution across Northern Africa. Today the Turkish Straits are administered by Turkey, a NATO ally, in accordance with the Montreux Convention, which imposes a principle of fair access for multinational shipping. Turkey’s administration has been responsible, and not disadvantageous for any party; but Russia chafes under a maritime access regime on her southwestern flank that is approved by the West, and administered by an outside actor. As outlined here, Turkey’s NATO orientation is not so secure as to eliminate concern about a realignment in this region – nor is her status as a secular regime, one not ruled by politicized Islamists.

Only Americans could contemplate these dynamics and not recognize the threat they pose to our national security. We cannot tolerate a Europe intimidated and in thrall to Russia from the East, and from a Northern Africa effectively ruled by Iran to the south. Each time we have tried getting along with a hostile Europe, we have had to go to war to remove the condition. But we cannot even tolerate a Mediterranean questionable for trade: seeking to redress such a condition was the first expeditionary military mission our young republic was moved to mount.

All of our global alliances are affected by the security of the Europe-Asia-Africa crossroads, however. Everyone depends on access to it, very much including Japan, South Korea, Australia, and India. America’s utility as an ally will stand or fall with our commitment and ability to keep the great crossroads secure and open for everyone’s trade access. (As it will for our Far Eastern allies with a similar commitment to the South China Sea and Strait of Malacca.) If an Asian power can make others pay tribute to access the waterways of the great crossroads (including the reserves of fossil fuels in the Middle East and Africa), and America cannot break that toll-demanding scheme, it is we who will be marginalized, and alliance with us that will be stepped away from. Regardless of whether you think we can survive that economically – we cannot survive it geostrategically.

The stakes in this game are very high, of course, which is why Russia and China will not let Iran play it alone. China cannot tolerate a Russia-Iran axis that excludes her, through a set of geographic blocks, from exerting a countervailing influence in the great crossroads. Russia, of course, is wary of all China’s forays into the region, for the same reason. As Iran’s regional activism increases, the competition between Russia and China to reap benefits from working with Iran will heat up further. Nations from Kenya to Saudi Arabia to India to Indonesia will be presented with choices both alarming and seemingly insignificant all along the way, and are likely to see their self-interest lying, increasingly, in affiliation with one or the other Asian competitor.

Amir Taheri’s title assessment is valid: this race is on because the US is perceived to be in retreat, and leaving a vacuum of geopolitical leadership in the great crossroads. As time goes by we are likely to blame Obama and his generic stances for this more and more. But it is also a phenomenon induced by a shifting tactical boresight, over the last 20 years, on microcosmic regional problems: “the Balkans,” “Somalia,” “sanctions on Saddam,” “transnational terrorism.” The global view America was able to revert to, often unconsciously, during the Cold War, has at least partially disintegrated since the demise of the Soviet Union. How often have we recognized that any solution in the Balkans reverberates through the halls of power in Moscow and Ankara? That leaving Somalia in disarray is an open invitation to Iran, Russia, and China, to establish a presence on one of the world’s two most important – and most vulnerable – chains of maritime chokepoints? That Iraq and Iran have both figured, in the minds of Russian and Chinese strategists, as gateways to the great crossroads; and whatever we do there amounts to swinging the gate one way or the other?

We had much more clarity on this region in the wake of WWII, when Stalin menaced it. But we saw his actions through the prism of Stalinist ideology, when a more permanently useful perspective is that they were classic hegemony-seeking, based on persistent geography. The state shows no signs of withering away: Marxists and Islamists, when they get in charge of one, will act like national rulers and seekers of regional power. The enduring truth is that if we, the US, want to hold the great crossroads open for trade, and keep its approaches quiescent, and unmenacing to our trade and our allies, we have to maintain a presence there: a presence designed and committed as much to securing that outcome as to addressing any single problem of the region.

It is not good enough to try to bribe or argue Russia, Iran, and China out of pursuing their regional courses. We can offer them nothing that they want as much as they want to control the great crossroads. Our only option, if we want to retain our security, trade, and alliances, is to be the hegemon of the great crossroads. Nothing else will work.

Great post. I’m ashamed to say that I didn’t look at Iran in a geographical context before, and you’ve summarized it very well. Thank you…

[This post and previous two: font fine.]

Thanks, Greg Inman. I’m glad it was of use.

A.Reader — I appreciate you getting back to me on the font. I actually haven’t changed my drafting methods, but WordPress has started translating my new posts into this font. No idea why. But I’ll make a note of what it is.

Very hard to read – not because it was anything less than perfectly clear and precise – but because the implications seem so dire. Obama’s overall approach seems to equate with “if we oppose them only half as hard, then they can have twice as much and nothing will change.” It would follow that if we surrender completely, we’ll have won!

Let’s say that the worst case scenario envisioned by Taheri and yourself comes to pass, that Iran occupies the power vacuum created by a US retreat, at least in degree, from the “crossroads”. What would the activities and relations of the states involved be?

First of all, intrigue has been the name of the game in the middle east for all of recorded history, no matter who was running the show. Just as the Muslim Brotherhood came into existence in Egypt as an underground religious response by the powerless to a semi-secular regime devoted to its own survival, any successful Iranian/Shiite encroachment on existing societies will inspire similar activity. We are constantly subjected to the myth that the US is the “Great Satan” in the middle east. However, if we did not exist, someone else would occupy that role. Moroccans, Turks, Somalis, etc., would have no problem regarding the pugnacious Persians as supercilious interlopers. Even now, intelligent members of “crossroads” governments must know that US hegemony is preferable to that of Russia, China or Iran. After all, they are able to see and analyze the same things we do. Russian policy toward Ukraine, for instance, shows what happens when there is a disagreement with that state, which seems to have preserved some of the worst aspects of totalitarian socialism while adopting the most wild west aspects of capitalism, gangster economics.

So, maybe we should retreat a little. Maybe we should let the mullahs colonize a place like Eritrea. Let them expend a fortune trying to subject the place while we finance a resistance that saps them economically and creates a peace movement in their own society.

However, this is a different issue entirely from a nuclear Iran. That will require a different kind of creativity.

what drivel. iran is an economic basket case that couldn’t effectively project power to a country that neighbors it (iraq) and we’re supposed to believe they’re on the verge of overthrowing regimes in egypt, morocco, and lebanon and conspiring with the russians and the chinese to form a new global empire? are you high? or just really, really stupid?

and i’d note that america’s collapse isn’t a “perception” it’s a cold hard fact. maybe it’s explained by the fact that people as myopic and idiotic as yourself were doing “intelligence” analysis in the armed forces.

Congratulations, OC. We should all aspire to be rebuked by the likes of YAI as often as possible.

Thanks, CKM. I was rather proud of that myself. I did want to congratulate YAI for using “you’re” correctly, which so many don’t do in these deteriorating times. I’m sure the absence of the apostrophe is due to a charming personal affectation.

chuck martel — Certainly, I have no illusions that Iran could achieve hegemony over the crossroads and get the place “organized” in any positive way.

No one has ever succeeded in organizing and holding the whole crossroads. Rome came the closest, but held sway only briefly. By the time the Ottoman empire had succeeded Eastern Roman Byzantium, the European trading and exploring powers were already on the horizon, preparing to drive the maritime wedge through the crossroads that has kept it out of the hands of a single power for the entire period of post-Middle Ages globalization.

The problem with just sitting back and waiting, though, is that the place does go down the tubes while you do that. That’s to the advantage of Iran and Russia, not to ours. Iran and Russia don’t need to have the stability and order we prize: armed turmoil works better for them, as long as we’re not stepping in to settle it down.

The thing Americans just refuse to realize is that Iran’s focus is on getting rid of something in her region, and that something is us. The constructive view of what to do with a great crossroads “caliphate” is much fuzzier for the mullahs. This is what Iran needs: radicalism in the population, and a pretext for getting Qods forces and missiles into key territory. That’s what will start making the crossroads too hot for us.

Iran doesn’t NEED stability and consensus about Iranian rule in her Arab targets. That’s not what she’s shooting for. She needs to make us run away.

That outcome depends mainly on us, of course. We don’t have to run when things get hot. But if we stay, and push back against Iran, it will have to be for our own vision and purposes, and the only posture that will work is one of strength.

As you imply, the Arab nations Iran has been trying to subvert don’t want us there because they like us and we’re such swell guys, but because it’s better for them if we are the hegemon and Iran is not. Therefore — and this is where many Americans always stick — we have to BE the hegemon. If we’re not performing that role, there’s no point for the local nations in throwing in with us.

It’s to our credit that wanting to be a hegemon is NOT our default national position. We tend to become one absent-mindedly. But our maritime hegemony of the great crossroads would be very easy to lose, and very hard to get back — and millions of people would be subjected to much, much worse than they are today, if Iran can promote radicalized insurgency and turmoil while America is off playing Obamanation.

Of course we can’t walk away from an area as important as the middle east and we can’t sit around there, either. It just seems that we could be less predictable, that we could investigate more options. Historically, when we have operated in an unconventional fashion, the mastodon media has come unglued when they discovered it, but just the same.

In the middle east, we’ve removed the set piece battle from both the jihaadi and Iranian playbooks. As long as we have our current deployment available, both those adversaries would be suicidal to concentrate troops in any numbers. The televised Iraqi disaster must have made a big impression on them. They are forced to disperse among the civilians and hide in remote areas because to do otherwise is to die. When they did concentrate, like Fullujah, there might not have been enough survivors to relate stories around the campfire later.

If you were an Iranian general and the political leadership instructed you to develop tactics that would allow your unit to oppose a coalition attack successfully and survive, what would you do? Weasels like Bashar Assad, with his fourth rate military, exist only because the US curries the favor of similar non-entities world-wide. Allowing him to have any credibility is charity.

As an aside,have you read “The Secret War Against Hanoi”, by Richard H. Schultz, Jr.? He talks about programs like the “Eldest Son” project, that involved scattering explosive AK-47 ammunition where the enemy could pick it up. We’re probably doing that in Iraq now.

Interesting post – Thanks.

A small point, but Bahrain is an island. The nearby peninsula is Qatar which also hosts US forces.

http://www.asia-atlas.com/qatar.htm

excellent poste, complet et bien détaillé, ça me plaît !merci bien

Je vous en prie, Tunisie hebergement. Bienvenu!

J’ai aimé bien la Tunisie quand je l’ai visité pour des projets communs avec les Marines Nationales des USA, Tunisie, et France. Beau pays, peuple exceptionnel.

Faites un retour souvent au blog de l'”Optimistic Conservative.”

The Guam Base Buildup is a joint venture of the American, Japanese, and Guam governments and will accommodate the influx of nearly 35,000 military and civilian personnel.