What are the implications of the extensively documented fact that agents of the Soviet government were employed in high positions in the United States government in the 1930s and 1940s? Do we have a skewed view of World War II because we have failed to address that question? If our perspective changed, would we judge that we didn’t even win World War II – but, to be more accurate, Stalin did?

What are the implications of the extensively documented fact that agents of the Soviet government were employed in high positions in the United States government in the 1930s and 1940s? Do we have a skewed view of World War II because we have failed to address that question? If our perspective changed, would we judge that we didn’t even win World War II – but, to be more accurate, Stalin did?

Diana West’s remarkable new book, American Betrayal: The Secret Assault on Our Nation’s Character, compiles some potential answers to these questions. As West argues early in the book, the American mind has become accustomed to the delinking of fact from implication – in large part, although we don’t see this connection, because of the troubled history of public revelations about Soviet infiltration of our government. She cites, as a model, the line of obfuscation that has protected the reputations of men like Alger Hiss, Robert Sherwood,* and Harry Dexter White – all proven Soviet agents – by deflecting, not disproving, the fact that they were Soviet agents, while focusing attention elsewhere, typically on attacking the character and motives of those who exposed them.

But that line of obfuscation has done something even more important than blacken the names of Whittaker Chambers, Martin Dies, and Joseph McCarthy. It has succeeded in preventing three generations of Americans from considering the implications of the fact that our national government was infested with agents of the Soviet Union. What does it mean about our policies, that these men were so involved in making them?

World War II

West highlights some specific areas in which we may deduce what the implications were. Probably the easiest to prove is the nature of the Lend-Lease program. If you’re like me, you were taught in grade school that Lend-Lease was designed by Franklin D. Roosevelt to arm Britain for the fight against Hitler, since he couldn’t get the U.S. into the war in its first years. Some amount of support went to the Soviet Union, once we became allies. But the emphasis in educating America’s children on the program, in the decades since World War II, has been on the arming of Britain.

West’s research turned up a very different picture. Lend-Lease, whose biggest beneficiary was the Soviet Union, was a unique program which bypassed Congress to allow FDR to send arms wherever he thought best. Shortly after Hitler invaded the USSR in June 1941, Lend-Lease began heaving huge amounts of arms, supplies, and even intelligence on the United States at Moscow.

West provides evidence that Lend-Lease, besides creating a pipeline in which intelligence on U.S. military and industrial facilities could be funneled to the Soviet Union, was also the vehicle for providing American support to the USSR’s nuclear-weapons program – including a shipment of uranium to the Soviets honchoed in 1943 by Harry Hopkins, FDR’s closest advisor during the war.

But Lend-Lease did more than hemorrhage intelligence (and, as West also reports, facilitate the entry of Soviet spies into the U.S). Lend-Lease prioritized massive quantities of arms for the Soviet Union as well – prioritizing them over arms and supplies for U.S. and British forces.

Citing earlier sources – we have known these things for a long time – West outlines how aircraft and munitions flowed uninterrupted to the Soviets during the Battle of the Philippines in late 1941 and 1942, when Douglas MacArthur needed but could not get air reinforcements, and eventually had to evacuate, leaving the U.S. protectorate of the Philippines to its fate. Indeed, in the fall of 1941, a big shipment of 200 aircraft that was intended for the British forces defending Singapore was diverted to the Soviets in the Lend-Lease pipeline, along with a shipment of tanks. Singapore fell to the Japanese in February 1942.

FDR told U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau in March 1942 – incident to an appeal from MacArthur for support to the U.S. and Filipino troops fighting on Bataan and Corregidor – that he “would rather lose New Zealand, Australia, or anything else than have the Russian front [i.e., the front with Hitler in the western Soviet Union] collapse.”

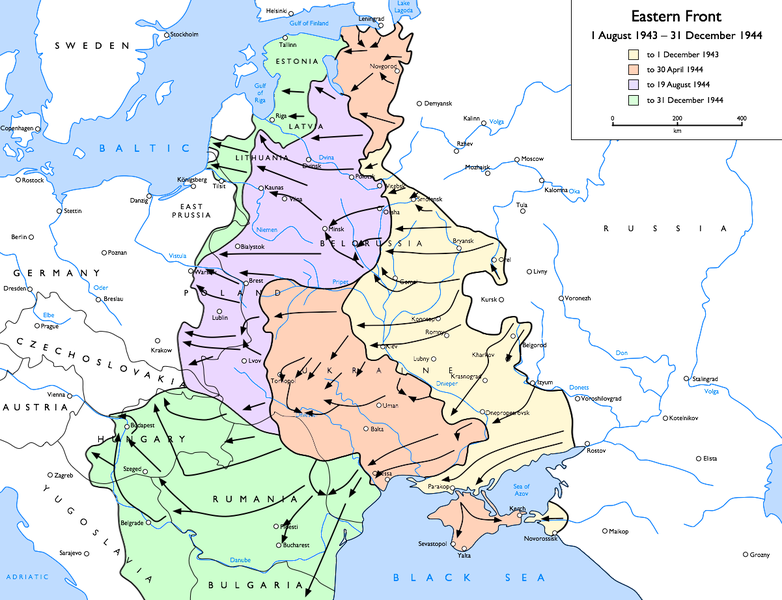

Was the Russian front in danger of collapsing? That’s a good question; by March 1942, Soviet troops had pushed the Germans back from Moscow and had them retreating toward Vitebsk, Smolensk, and Kursk along the northern portion of the front. Later, in August 1942, the Germans would launch Operation Blue and drive to their furthest point of advance into the Caucasus – almost to Grozny, in Chechnya – in the south. (The Battle of Stalingrad was part of this advance.) Hitler hoped to secure the Caucasus oilfields with this move, recognizing that with the United States in the war, his link to North Africa could be in increasing peril. (American troops landed in North Africa in November 1942.)

If there is a weakness in West’s treatment of her topic, it lies in the fact that she doesn’t fully address the war context in which FDR was making decisions (or, at least, his advisors were). She makes a very commendable effort to do just that regarding some of her points; e.g., regarding the Allied decision to conduct the D-Day invasion. On the question of how close the Russian front was to “collapse,” however, the book doesn’t outline a context for making that assessment in early 1942.

Stipulating that hindsight is not available to decision-makers, we can note that Soviet forces, reinforced from the Far East, and having received Lend-Lease supplies for at least six months at that point, had been able to mount a successful counteroffensive on the most strategically important 300-mile stretch of an 800-mile front. Moscow was in no danger of falling, by March 1942; whether any portion of the Soviet front line was in danger of “collapsing” – or, indeed, what FDR even meant by those words – is harder to say.

But West will get pushback on her book, from knowledgeable people of goodwill who have lived for many years with the standard narrative of World War II in their heads. If FDR prioritized supplying the Soviets over supplying U.S. and British forces in Southeast Asia, they will say, that was because of his war strategy: a strategy we have long known about and recognized as part of the narrative. What’s the big deal? Yes, we knew FDR decided to focus our effort on the European front first. Analysts and historians have been thrashing out the question of whether he should have for decades. Does West’s book add anything new?

The impact of Soviet influence

I find that it does: first, because it brings multiple events and threads of activity into focus at the strategic level, in a way most treatments of World War II have not; and second, because it emphasizes and inspects in detail the FDR administration’s focus on the Soviet front with Germany. In telling ourselves the narrative of the war, Americans have tended to gloss over that aspect of it. We have, moreover, focused on the great battles, typically painting in no more than a few contextual strategic strokes around them. What Diana West does, in effect, is survey the landscape of the war from that higher, strategic level, and ask, “Why?”

Building her case for Soviet penetration of the FDR administration, she points out that Harry Hopkins, he of the uranium shipment to the Soviets, took the extraordinary action in 1943 of personally warning the Soviets that the FBI had a particular Soviet agent under surveillance, after he was officially advised of that fact by J. Edgar Hoover. Also in 1943, the Soviet foreign minister, Maxim Litvinov, presented the White House with a list of individuals in the U.S. State Department whom the Soviets wanted removed from their positions – and within a couple of months, all of those individuals were gone. (These events are documented.)

Did this level of Soviet embeddedness in U.S. government operations have no consequences for our war-strategy decisions? Consider the context of the decision to mount the Normandy invasion in 1944 – after Allied forces in 1943 had driven into southern Italy and secured Rome’s surrender. Allied military planners at the time made a strong case for coming at Germany from the south, on the ground primarily through the Balkans in the East, and in the air, moving bases gradually closer from the redoubt of southern Italy, as well as flying from Britain across northern France. The Soviets were the loudest voice against this course, insisting that the new front must be opened from the northwest – that no other front opened anywhere would do the trick.

Now consider, as West asks, that in 1942, 1943, and 1944, high-ranking Germans who opposed Hitler made multiple overtures to the Western Allies to negotiate a German surrender: one that would in each case have involved removing Hitler from power while averting a Soviet advance into Germany. FDR stonewalled each one of these overtures, declining to respond in any way.

Meanwhile, Soviet propaganda themes, inaccurately reflecting German opposition groups as weak, corrupt, and feckless, were being faithfully repeated by an analyst at the German Desk of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the wartime intelligence agency. Franz L. Neumann wrote dismissive, pejorative intelligence assessments of the German resistance – because he was, in fully documented fact, a Soviet agent, working for the KGB. (As West notes, Neumann was also an early member of the “Frankfurt School” of Marxist social theory.)

Now reflect that in January 1943, when the Soviets were successfully driving the Germans out of the Caucasus – pushing back Hitler’s “Hail Mary” to get to the oilfields – while U.S. troops were fighting in Guadalcanal, New Guinea, and North Africa, and preparing for the invasion of Italy, Lend-Lease managers in the U.S. were given the following directive:

The modification, equipment, and movement of Russian planes have been given first priority, even over planes for U.S. Army Air Forces.

Would the combination of these factors begin to color our view of “FDR’s strategy” to win World War II? In light of them, what exactly did “winning” mean to FDR? Why did FDR’s concept of winning World War II require that Stalin’s forces be armed for a drive across Eastern Europe? That was the basic end his policies all combined to serve.

Yet, objectively, it is entirely possible to conceive of an alternative strategy. Churchill had one in mind throughout the war, favoring the plan for the Western Allies to attack through the Balkans. Of course, the alternatives of either negotiating a German surrender before D-Day, or mounting a Western Allied drive through the Balkans, would have preempted the Soviet drive across Eastern Europe. There’s no escaping that fact, however else we explain FDR’s decision, or derive implications from it.

What happened in World War II was not fated; it was decided upon. There is nothing conspiracy-obsessed or insubordinate about second-guessing FDR’s strategy for World War II. The bottom line is that his strategy – his strategy – is what enabled Stalin to occupy Eastern Europe for the next 45 years. FDR not only gave Stalin the time and space to occupy Eastern Europe, he gave Stalin the means to do it. West quotes Khrushchev to the effect that Lend-Lease enabled the Soviet drive from Stalingrad to Berlin, but we don’t really need one-liners from Khrushchev to know that. Any objective analyst surveying the facts about the Soviet Union’s economy and overall situation would have to come to the same conclusion.

The American mind

Yet Americans have an entirely different narrative in our minds about World War II. With all the dense parade of facts and intensive footnoting in American Betrayal, its most powerful intellectual impact comes from West’s thesis: her abstract postulate about fact and implication. Why do we not recognize that FDR’s policies were designed to promote Stalin’s conquest of Eastern Europe, even though we know the basic facts that would cause us to at least consider the question? And what does that say about us?

Of most of the relevant facts, there was some level of public awareness at the time, or at least within a very few years afterward. There was no shortage of critics pointing out the consequences of FDR’s war policies. I recall as a teenager in the 1970s plowing through old books from the 1940s by James Burnham, the geopolitical analyst who in later life wrote for many years for National Review. Burnham – like many of the incisive anti-communists, a former socialist himself – foresaw very accurately in the mid-1940s what would happen to Eastern Europe, and why. West cites the critiques of others who understood, at the time, that the Allied victory in Europe in effect exchanged one brutal, collectivist hegemon for another.

But why Americans, in particular, wrote a different narrative about World War II and its aftermath remains an open question, I think. I don’t disagree with West that the Soviets and their handmaidens in the free world sought to influence our thinking about the war. The benefit to them from a deceptive narrative – one in which fact and implication never intersect except by their ideological approval – is obvious. But I think West gets at the most important factor of all without giving it the emphasis she gives to the panorama of Soviet-agent shenanigans. That factor is what, with our own free will, we chose to do.

The Reagan difference

I wouldn’t say on this topic that I part company with Ms. West’s analysis. But, having been a student of Ronald Reagan for so many years, I choose a different emphasis. Reagan behaved as if our motives and actions were what was most important. And by doing so, he achieved remarkable political successes at a time when Americans had been slowly buying, for over three decades, into a Soviet-serving narrative about social reality, World War II, and the trend of history.

Reagan would have agreed that, per the old military aphorism, the enemy – including the Soviet agent in the United States – always has a vote. The enemy’s actions and intentions do affect what we propose to do. But our decisions are ultimately governed by our priorities and attitudes, not the enemy’s.

Applying this axiom to the actions of the great majority of Americans who weren’t Soviet agents in the 1940s is something of an exploratory expedition into an undiscovered country. Perhaps the simplest explanation may turn out to be true: Soviet-sponsored lies about what was going on in Washington, D.C. were successful because the American people had so many other things in life to worry about. There were plenty of citizens – like my maternal grandparents – who distrusted FDR and supported the investigations of Communists in American institutions. But who had the leisure to turn this perspective into a politically successful movement?

I think there is truth to the case West and others make that the U.S. and the West didn’t defeat communism. But the U.S. did defeat the Soviet Union, and did thereby win the Cold War. Doing so dealt a body blow to communism as an organizing rubric for international predation. The reason why is something Reagan recognized clearly – just as Stalin recognized it, if for a morally opposite purpose: that ideologies and beliefs must hold territory, if they are to thrive and wield power.

Reagan turned the battle against a predatory communist ideology into an offensive struggle for the enemy’s own key territory – and Reagan was sure that we would win the struggle, because he took as a given that the evils of communism would be rejected wherever people were afforded a meaningful choice. He was right. His accurate prediction was not, moreover, about populations that had the unique libertarian characteristics of the United States, but about peoples who had never been as free, nor dreamed of being as free, as Americans have. Indeed, they were people who had been intensively indoctrinated for decades in Big Lies. There was hope even for them.

This matters because Reagan is the great exception to the rule that collectivism in its various guises – communism, fascism, Nazism, socialism, progressivism; “liberal fascism,” as Jonah Goldberg calls it – has been winning a war of attrition against the spirit of classical liberalism for the last 100 years. Not only did Reagan strike a death blow to Soviet communism – which no longer exists as an organized global predator – but his public, in liberated Eastern Europe as in America, remembers him accurately as having done so. At least for now, Reagan has beaten the odds against the liberal-fascist framing of history, which is more than can be said for the narrative of World War II.

The conflict of visions

The question is how to relate that to the problem Diana West propounds. In the larger context of our effective abandonment of logic, fact, and implication, the governments and reigning public ideas of the Western Left have come to resemble 20th-century communism to such an extent that there seems no point in distinguishing between them. Who really won World War II, after all, if the European Union is as ideologically collectivist as the old Soviet Union? Who really won the Cold War, if America is in the last stages of collectivization as I write, even though the old Soviet Union is gone?

Here again, I think West brings forth an important idea. She frames the conflict between collectivism and classical liberalism as one in which the body of Western beliefs – being open to evidence and not consciously ideological – has been somewhat defenseless in the face of a well-organized ideology. In her formulation, Western liberalism is not an ideology. Therefore, it doesn’t fight like one.

I don’t think this fully explains the imbalance of momentum between the two, however. I agree with West in fingering the ideological struggle as a point of vulnerability for the West. But I’m not convinced the distinction she proposes fully captures the issue. Must Western ideas be fated to extinction because they are subject to skepticism and empiricism, and are perhaps, therefore, reversible? If they were, how could they have survived up to now?

Again, Reagan suggests the answer, if we are willing to see it. Western liberalism is actually backstopped by irreducible assumptions, not just about the sanctity of human rights and dignity, but about the positive power of releasing our fellow men to liberty – if we base it on the Judeo-Christian idea of a merciful and provident God, one who designed us for good. Take God away, and our beliefs are backstopped only as far as the next election. Skepticism and lack of belief demonstrably do not stand up effectively against collectivist ideology as an organizing principle for communal life. But that does not mean that rational liberalism can’t. The question is what its foundation is.

There will be some who disagree with this last point. But it remains the case that the only U.S. president who changed our policies and achieved a different outcome in the Cold War was the one who philosophized about freedom – unabashedly, and often – from the perspective of this Judeo-Christian belief about God. Reagan followed in the footsteps of a line of Western philosophers, including America’s founders, for whom it was not empirical uncertainty but philosophical certainty, based on their understanding of God, that made them insist on limiting government’s collectivist imperative and privileging the individual over it. It was because of his belief in God that no Big Lie could confound Reagan on the topics of individual freedom and the evils of communism.

He was called the “Teflon president” in part because he spoke right past the Big Lies, as if they had never been told and needed no refutation. Reagan wasn’t known for debunking the Big Lies of communism. He was known for the positive ideas he espoused: freedom, limited government, the liberation of captive peoples. His political success amounted to an occupation of territory, a sort of reversal of Diana West’s “Soviet occupation” of Washington, D.C.: he simply took over the reigning political narrative, rather than fighting against someone else’s.

His success was by no means total, of course, even inside the United States, where entrenched bureaucracies guaranteed, before he was even sworn in, that Big-Lie narratives would outlast the Reagan tenure in the Oval Office. The seeds had been sown much earlier of the “governmentism” that would imperil Reagan’s purpose, and make it seem almost impossible that his impact would be enduring. West is right to warn that the overall course of the American ship of state has not really changed since at least 1933.

The cycle of history

But does this signify that the Reagan difference was meaningless? What I would propound, to frame this issue, is a pattern of human tendencies against which the liberal-minded of each generation are always battling. We – Americans, especially, but all Westerners to some extent – are apt to imagine a progressive quality to human affairs, one in which the battles we win need not be fought again. In this imagined context, Reagan’s victory over the Soviet Union settled the great question of the 20th century, collectivism versus liberty, once and for all.

But if we understand that the same old threats and complaints keep arising from human nature, and only the technology and slogans change, we can see more clearly that battles can be won and they do matter, but that they will have to be fought again and again – if sometimes on different ground.

There was nothing really new about the motives of Soviet communism, and not all that much new about its methods. Technology enabled the Soviets, as it did the Nazis, to scale new heights of effectiveness. But the urge to corral, organize, and dictate to one’s fellow men – and to do it in large part by subverting people’s perceptions and decision matrices – has always developed along the same old lines, from the Jacobins back through the schemers of late-Imperial Rome to the verbose demagogues of ancient Athens.

It isn’t possible to breed, train, or legislate this urge out of humankind. It can only be perpetually guarded against; or, even better, preempted – temporarily, within a given generation. As satisfying as the rare game-changing victory is – e.g., the founding of the United States, the victory over the Soviet Union – it is never “Game over” for the human urge to power. We will have to fight the fight again. What we must learn is not only how the collectivist enemy works, but what we have done in the past that was successful.

West is undoubtedly right about the resurgence of the Big Lie method, with Islamist advocacy in the U.S. government, academy, and media. And she is right that the less we understand what’s going on with it, the more our minds are corrupted by its deceptions, and by the rampant disconnects in its narrative between fact and implication.

Preparing the battlefield

I find reason for optimism, however, in what Reagan was able to accomplish in ending the Cold War. Reason for optimism, and a glimmer of the answer to our current problem with the Big Lie. As important as intellectual hygiene is, people don’t really navigate their way to positive, life-giving beliefs through the systematic debunking of lies. That’s not how we have our minds renewed. In fact, getting the perspective of wisdom and sound judgment on Big Lies typically requires having solid prior beliefs about what is good and right. Without those beliefs, recognizing the Big Lies just drives us to despair.

But the incandescent ideas of liberty, small government, and natural rights are still there, having been formulated for us and left to us as a priceless legacy by our forebears.

We can’t expect others – certainly not those in the Islamic world – to want our ideas if we are not living by them. We can expect that our heritage of ideas will be incessantly attacked and lied about, as it has been for at least 150 years by the communists and liberal fascists.

But if we emphasize speaking the truth about those ideas, at least as much as we emphasize debunking the Big Lies around us; and if we decide to live by the ideas again, rather than only pretending to do so and then misunderstanding the results that come from that pretense – if we will do those two things, we will, perforce, set up another war for territory between good and evil. It may or may not have to be waged on our own territory. That will depend on how soon we correct our course. But, as Reagan demonstrated, a war for territory – a war to occupy territory with the positive benefits of true liberalism – is a war we can win.

In the meantime, read Diana West’s American Betrayal. It is well worth your time. It will make you see the present with fresh eyes, as well as the past – even if, like me, you started out aware already of the Soviet agents and the contemporary criticism of FDR’s war policies. American Betrayal relies on extensive documentation, but it is a polemical work: it is meant to change your mind. And it will.

See here for a video of Diana West’s talk about American Betrayal for Children of Jewish Holocaust Survivors in Los Angeles on 10 July 2013.

* Ms. West has reminded me that Robert Sherwood (who headed the Office of War Information) was not among the Communist agents of the Soviet Union. Including his name in the list was sloppy of me. Of several hundred such agents in the FDR administration, Lauchlin Currie, who served on the White House staff, is another especially notable one. There is a long-running dispute over whether Harry Hopkins, FDR’s closest advisor, was a Soviet agent. It is virtually impossible to prove the negative; evidence for the proposition has come from several sources, including the categorical assertion of KGB defector Oleg Gordievksy that Hopkins acted on behalf of the Soviets Union. See here and here for more.

J.E. Dyer’s articles have appeared at Hot Air, Commentary’s “contentions,” Patheos, The Daily Caller, The Jewish Press, and The Weekly Standard online. She also writes for the new blog Liberty Unyielding.

Note for new commenters: Welcome! There is a one-time “approval” process that keeps down the spam. There may be a delay in the posting if your first comment, but once you’re “approved,” you can join the fray at will.

This is so excellent, Jennifer. Did you send it to Diana? Doris

Sent from my iPhone

I remember watching the military channel, about the second World War and they stated that Russia defeated the German’s in WW2. Not the Allies, but the Russians. Hitlers biggest mistake was taking on Russia when he did. He should have made them an axis member instead of Italy. Or have them both, allies. All of Europe, Middle East, Africa and Most of Asia would be speaking German, if it wasn’t for the United States. Senator Joe McCarthy was right. He just made the mistake of calling them what they were, Communists. He should have called the Progressives, which are what they are called now. He wasn’t crazy like they like to make him out to be. He just knew the truth and was not afraid to stand up and say it.

Just a footnote to a very interesting piece.There were some geopolitical victories regardless of the concessions made in Eastern Europe.

Think of what the Soviet position would have been if Churchill hadn’t managed to secure post war Western interests in Greece (90%) and Yugoslavia (50%), and if the US hadn’t followed up with the Truman Doctrine.

Soviet Navy/Air Force in Souda bay and the Adriatic coast bases, Turkey, the Bosporus and the whole of the ME cut off, maybe no Israel.

The world would be a very different place.

I´m not sure about the timeline but the Soviets got enormous amounts of supplies in exchange for their extremely late, low-risk and really unneeded declaration of war on Japan. That was when the war in Europe had already ended. Why? Whatever was at work here, it was not cold blooded realpolitik. FDR saw himself as an antiimperialist agent of change. Not exactly an un-American attitude, but he bought into a naive view of the Soviet Union (and the British empire). It had the practical result of condemning much of central Europe and Asia to poverty and war.

It sounds shocking to most people, but if the US had used the threat of nuclear weapons to insist on a free, non-communist Europe, it would have been a blessing for countless people. That is an objective fact.

I spent two years in the Army in Germany. Fantastic people by the way. The only thing I found that the Germans were up set about, was splitting up Germany. A lot of ex German Soldiers said that they would have surrendered to American forces, but not Russian forces, an could not understand why the U.S. Army didn’t keep advancing. Even General Patton couldn’t understand it. That’s why he was killed. He said we might as well go though Russia, while we were over there. That’s why he was killed. Hell, the military industrial complex was making too much money off the war. Same way with Korea, Vietnam, and every war or conflict after them. We sacrificed some of our soldiers in the Pacific to make sure most of Europe didn’t have to speak German. The Chinese even charged us a million dollars to let us build an air field in China to fight the Japanese. Then ask me why we would even bother going into Vietnam, after the French got their asses kicked. General Douglas MacArthur said the we could never win a ground war is South East Asia. The same thing in Afghanistan and any of the other Countries over there. We are just wasting our Men, materials and money over there. You will have to forgive me if I strayed a little off topic. Like our own government giving our Enemies(Egypt freedom fighters) tanks and planes. I will be surprised if that doesn’t come an bite us in the ass.

Patton wasn’t killed because he couldn’t understand why he wasn’t allowed to keep advancing. That’s hogwash.

“On December 8, 1945, Patton’s chief of staff, Major General Hobart Gay, invited him on a pheasant hunting trip near Speyer to lift his spirits. At 11:45 on December 9, Patton and Gay were riding in Patton’s 1938 Cadillac Model 75 staff car driven by Private First Class Horace L. Woodring when they stopped at a railroad intersection to allow a train to pass. Patton, observing derelict cars along the side of the road, spoke as the car crossed the railroad track, “How awful war is. Think of the waste.” Woodring glanced away from the road when a 2½ ton GMC truck driven by Technical Sergeant Robert L. Thompson, who was en route to a quartermaster depot, suddenly made a left turn in front of the car. Woodring slammed the brakes and turned sharply to the left, colliding with the truck at a low speed.[172]

Woodring, Thompson, and Gay were only slightly injured in the crash, but Patton had not been able to brace in time and hit his head on the glass partition in the back seat of the car. He began bleeding from a gash to the head and complained to Gay and Woodring that he was paralyzed and was having trouble breathing. Taken to a hospital in Heidelberg, Patton was discovered to have a compression fracture and dislocation of the third and fourth vertebrae, resulting in a broken neck and cervical spinal cord injury which rendered him paralyzed from the neck down. He spent most of the next 12 days in spinal traction to decrease spinal pressure. Although in some pain from this procedure, he reportedly never complained about it. All non-medical visitors, save for Patton’s wife, who had flown from the U.S., were forbidden. Patton, who had been told he had no chance to ever again ride a horse or resume normal life, at one point commented, “This is a hell of a way to die.” He died in his sleep of a pulmonary edema and congestive heart failure at about 18:00 on December 21, 1945.”

We went into Vietnam because of the domino theory, we escalated our involvement because LBJ was not going to be the first American President to lose a war.

MacArthur was wrong, about a lot of things. We could have won militarily in Vietnam and in Afghanistan, it was politics that prevented winning.

As for Egypt, if the army retains power, those weapons won’t be used against us.

I am some what of a history buff. Now there was a story about how Patton was killed in the Spot Light news paper that was put out by the Liberty Lobby. Will provide more info. if needed. He was assassinated, i believe by the Russians, with our military help. The story for what 50 or so years was that his car had an accident with a farmers wagon. Than not to long ago his car was involved in an accident with a deuce and a half. Which official version is right, the first one or the second. I know politics play a part in every war, but what makes you think that we could have won? Plus whats your definition of winning? Putting politics aside, what have we accomplished in Vietnam, Bosnia, Iraq and Afghanistan? As soon a we pull out, the Muslim Brotherhood and Sharia Law will be running things again. But they will have some nice hospitals and infrastructure to work with. I am going to quote an Egyptian that I talked to right after we invaded Iraq. He said we didn’t know what we were getting into. There are three sects there, Curds, Sunnis and Shiites, that can’t stand each other, and that most of them were ignorant f__king animals and that Hussein was running the Country the only way possible, through fear and intimidation. In the last 60 or so years what have we accomplished militarily? I guess you could say that we stopped communism is South Korea. Did we stop the Muslim Brotherhood in Bosnia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Egypt or an other Country were the Muslims are wiping out the Christians? All over Africa the same thing is going on. It took me a long time to realize that all there wars and battles were over religion. Plus we are supplying them with money and arms to do it. I imagine Israel will some day see the fighter jets and tanks that Obama is sending to Egypt.

No offence, but your comments reveal you to be as much a conspiracy buff, as a history buff. What makes me think that we could have won is that our effort in both wars was greatly hindered by politics and the ROE’s enforced upon our military.

My definition of winning is eliminating an enemies ability to resist and then imposing a peace whose conditions preclude future aggression. Japan and Germany being the foremost examples of such.

Our lack of accomplishment in Vietnam, Bosnia, Iraq and Afghanistan is due to two factors; the machinations of the left and our own confused thinking.

Our lack of progress in fighting Islamic aggression is entirely due to three factors; 1) a refusal by the West to face the basic and irresolvable, philosophic conflict between Islam’s fundamental theological tenets and classical western liberal values, which has led to our refusal to identify our enemy, which is mainstream Islam 2) our society’s embrace of a doctrine known as “Just War Theory”, which is responsible for much of our ROE’s and 3) that the reality of ME societal culture leaves but two choices; “the strongman” or jihadist Islamic States.

Why would LBJ worry about losing a war that he didn’t even start? We had advisers over there when the French were still there. Did you know that we(I mean the Government) knew when and where the Japanese were going to attack Pearl Harbor? They let them soldiers an sailors get slaughtered to piss of the American people enough, so we would get into the war. You really have to wonder why none of our aircraft carriers were at Pearl Harbor. They figured they could lose a few battleships, but they didn’t want to lose any aircraft carriers. I had an old merchant seaman tell me if I really wanted to understand what was going on, was to find out who financed Japan, Germany, Italy and England during the war.

Um .. No.. The Goverment (actually State, War, and Navy – there was no unified defense department in 1941) had a deep suspicion that the Japanese were going to do something, we had some intelligence and some information, but not enough to pinpoint an actual target and date.

1. The Japanese were excellent at hiding their intentions and we didn’t have enough pieces of the puzzle in enough common hands to know when and where they were going to attack, and we certainly didn’t know the means. Naval intelligence was just not “listening” to their early reports of the excellence and lethality of the Japanese Naval Aircraft, pilots, and tactics.

2. Most of our intelligence was diplomatic. It did suggest that the Japanese were conducting sham peace talks, and it did suggest that they were going to attack us. The information all pointed to a Western Pacific attack in the Philippines, Guam, and other Far East US coaling port holdings. Not until very late in the game did we even suspect that something would be done at Pearl.

3. We had no concept or notion at the Flag and Diplomatic level that the Japanese were going to launch a six carrier task force air strike at our main base in the Pacific. US Naval tactical and strategic thinking was still not “there” yet. We had some new forward thinking Admirals, and Captains; but we were still mired in the Battleship concept. The further thought that the Japanese would actually have the full spread of technology, daring, and capability to launch such an attack was still not a “normal” thought. (Prejudices do help to inform us when we are analyzing data).

Just ask Admiral Kimmel and General Short… They goofed and guessed wrong.

Occam’s Razor hovers boldly over this one. We were pointed at Europe, the Roosevelt Administration was more concerned with War in Europe, and the Japanese merely taking advantage of our attention across the Atlantic to deal with more of their military moves in the Western Pacific.

We were an isolationist, threat denialist nation as a polity, and racist to go along with it. The Japanese surprised us and kicked us hard at Pearl Harbor and the Philippines. They kicked the Brits hard in Malaysia, too. (and the conspiracy theorists keep bleeting that Churchill knew… sure.. like if the Brits knew, they’d want Malasia taken, and a huge number of combat troops imprisoned… right).

Try reading “At Dawn, We Slept” by Gordon Prange… it is a definitive and comprehensive look at the entire situation.

r/John – TMF

For what I have found out so far, the Japanese were using the Enigma code the Germans had. The Brits had cracked it before Pearl. The Brits in Singapore were reading the Japanese military communications before Pearl was attacked. Churchill told FDR about it. Who else in Washington at the time knew about it, I don’t know.

Nope. That’s one of those conspiracy theory… revisionist history falsehoods to avoid. The Brits new some things, but not very much… and had no big warnings other than what we had.

Some of this “stuff” is amazing.

They lost an entire army in Singapore… An army that they dearly needed to fight the Germans.

We made some compromises and as Diana West is demonstrating, especially that we were too cozy with the Soviets who had due to massive infiltration too much influence in our policy and strategic decisions.

The Japanese had their own codes, with their own encryption/decryption methods. The Germans were not fond of handing out Enigma machines to anyone… just ask the the Polish intelligence officers who were tortured and some died to protect the pre-war fact that they had done major work with pre-war industrial Enigma machines that they had acquired.

Enigma was never cracked by any nation. What was cracked was the method for transmitting the “keys” the rotors, settings, and plug board connections for the period. That was sent via more conventional methods. (Primary source on that one… and I am not saying who it was.)

Sorry… don’t believe everything that you read on the internet. Look at everything with a skeptical eye, and always apply Occum’s Razor. The simplest explanation is usually the most correct.

The Japanese were discounted for many reasons, and our conflict with them was a separate issue from Europe. FDR was concentrating on Europe, our “eyes” were across the Atlantic, and a war with The Empire of Japan was definitely not something that anyone wanted.

r/TMF

Let me know if I am wrong, but didn’t we shut off all the raw materials to Japan before the war?

There were so many despicable things done to the American people of Japanese decent, on the West Coast. Internment camps was the biggest. Who really profited by it, one was Randolf Hurst, who bought up the property of the people who were in the internment camps, and could not pay their mortgage’s. They lost every thing they had, because of the scare mongers. Did the Americans on the East Coast, get put into internment camps because they were of German or Italian decent? The U.S. is a lot closer to Europe than it is to Japan.

What happened to the Japanese was atrocious. However, there was a real threat within that very insular community. There were several organization “Secret Societies” that were critical to Japanese Imperial intelligence. These organizations existed in the West some dating before WWI (Japan was an ally back then).

The over reaction to what should have been a fairly normal war time law enforcement process of warranted observation, arrests, and military tribunal prosecutions… was twisted into the wholesale internment that most Americans are quite ashamed of today.

Yes, there were internment camps for German and Italian nationals and first generation families. The process for interning them was far less sweeping and general. More often than not those families and groups were labelled as “Enemy Aliens” and placed under strict observation.

War is messy. The US is a huge diverse, messy culture, and the war time administration played right up to the edge of Constitutional behavior.

r/TMF

Where were these internment camps for the Italians and Germans on the East Coast. I know they kept a better eye on some of them, but they didn’t round them all up an lock them away, like the did the Americans of Japanese descent. I know there were not as many Japanese Americans on the West Coast, as there were Italians and Germans on the East Coast. What you have to look at is who gain the most by locking up the Americans of Japanese decent. The ones in the Military that we sent over to Europe fought with honors for their country.(United States), While their Country was shitting allover their families and friends back here in the U.S..

Did any one go an lock up all the members of the American Nazi Party. That would have been a good start. But no they didn’t. There wasn’t any financial or political gain to do so. I do not have any Asian blood in me, but I have French, Belgium, English, Scottish, German and American Indian. Probably more that I don’t know about. But it just bothers the hell out of me, the way they were treated. Maybe its because I all way’s judge people by who and what they are, than by their race.

You mention detention camps on the East Coast for Americans of German and Italian heritage. If they locked up any one, it had to be some one that they caught doing espionage. Then they didn’t lock up their whole family. Where were these camps and did they lock up the whole family? They didn’t even bother to lock up the members of the American Nazi Party. Mainly because there was no finical or political gain to do so, as there was on the west coast with the Americans of Japanese heritage. There were soldiers of Japanese Heritage that fought with valor in the European Theater. They didn’t want to send them to the Pacific Theater, but the sent a lot of Americans of German and Italian Heritage to the European theater.

I have to apologize for replying twice. I didn’t think the first one went through.

“Why would LBJ worry about losing a war that he didn’t even start? …Did you know that we(I mean the Government) knew when and where the Japanese were going to attack Pearl Harbor?”

LBJ inherited Vietnam and subscribed to the domino theory. President’s are inordinately preoccupied with how history will judge them. LBJ’s determination to not be the first American President to lose a war is perfectly understandable.

The report on the possibility of a Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor did exist but never reached the higher echelons of our government. FDR was looking for an excuse for America to enter WWII because not to do so would ensure the victory of Hitler over Europe and Russia and, the dominance of Japan over the Western Pacific. It’s not a good idea to let yourself be isolated and surrounded by the bad guys…

The reason why none of our aircraft carriers were at Pearl Harbor is because they were on long planned maneuvers. Admirals don’t just suddenly decide to take the fleet out for a cruise at sea. The Japanese sneak attack no more survived its “first contact with the enemy” than ours do, there’s a reason why it’s a military maxim.

Oh, a merchant seaman, huh? The axis powers financed themselves. England was financed by the US. It wasn’t the Rothchilds, Rockefellers or illuminati… or Rosewell aliens.

Other than in fictional novels, the wealthy don’t manipulate world events, on the other hand, they do seek to maximize their financial gains, through leveraging their financial resources and social contacts.

The information on the Attack did reach Washington. Second, LBJ would have been the second to lose a war. Unless you think we won in Korea. The Rich did finance the War and reaped in the Profits. Rockefeller through Standerd Oil was selling oil, an oil products to the Germans as well as the U.S. Look at how much the Federal Reserve made. You still didn’t say who financed Japan during the War. Rothschild(Illuminati) helped to financed the European side, but who financed the Pacific? As far as Roswell Aliens, the crash happened after the war. But they could have been there during the war, and crashed on take off. So there is a chance they helped with the technology on radar, sonar and the bomb sight. Maybe even helped in designing some of our fighter aircraft. As far as your statement about the wealthy not manipulating Word Evens. I am sure you remember the battle cry, Remember the Maine. If history is right, Randolph Hurst had some thing to do with starting the Spanish, American War. Wars have been fought, but for no other reason than to reduce the population. Most wars fought today are Religious Wars. Well its more like Genocide, the Muslims wiping out the Christians and Infidel’s. This is going on world wide, not just in the Middle East. Right now we are helping finance the Genocide with the money, military supplies that the U.S. have been giving to the Rebel’s(in other words the Muslim Brotherhood.

I’ll be happy to discuss issues with you once you remove the tin foil hat. Until then, enjoy little your world.

I forgot to add I.G. Farben to the list of who financed WW2. Standard Oil supplied Nazi Germany with oil for a while during WW2. In 1940 American code breakers broke the Japanese Diplomatic Purple Code. Confirming Japan was preparing for all out war. The also formed the Tripartite Pact in Sept. 27, 1940. The U.S. shut off all supplies of raw material and oil to Japan. Which forced Japan to find other sources for oil and raw materials. I have been doing some research, an did you know that Adolf Eichmann was employed at one time by Standard oil? Also did you know that I.G. Farben, Standard Oil and General Motors were in business together in Germany before WW2. Also Henry Ford help set up some factory’s in Germany. Also I haven’t been wearing my tinfoil hat lately.

facing up to one’s denial is the first step to recovery.

That Merchant Seaman I mention, said that when the ship he was on docked in India during WW2, one of his co-workers had died and he went to his Hindu funeral there in India. He said that the Muslims were cursing and throwing rocks at the Funeral Precession. He was the one who got me to pull the wool off my eyes and take a look at the Muslim menace we face today. Also the plans to attack Pearl were not made over night, so the Navy had the foresight to make sure that the aircraft carriers were not in the Harbor, which wouldn’t be hard at all. Say you heard that some time in late November or early December they were going to attack. So it wouldn’t be hard at all to plan maneuvers to keep them out of Pearl.

Outstanding article which makes a strong case for the consequences of FDR’s policies. I remain unconvinced however on one major point. Namely that the Allies would have been better off attacking Germany through the Balkans. Looking at the map and the arrangement of opposing forces, two factors are obvious; the Allies could not have attacked Germany directly, as the alps stood in the way, so they would have had to swing east and then up through the Balkans, essentially substituting Allied forces for the Soviets and consequentially presenting Hitler with but one front to deal with, an important consideration.

The Allied invasion through France presented Hitler with two fronts, the classic caught between ‘the hammer and anvil’ and he could defend neither sufficiently because he had to divide his forces. That would not have been the case had the Allies attacked from the east, preempting the Soviet attack. Another consideration is that also would have resulted in far more Allied deaths as Allied forces would have been dying instead of Soviet forces.

Often in life and especially during crisis, the only choices are between bad and really bad. Arguably, FDR made the decision that defeating Hitler and the Nazi’s now demanded priority over the certainty that the Soviets would acquire Eastern Europe. It’s quite likely that FDR was advised of this and decided that the most certain path to defeat of the Nazi’s demanded the sacrifice of Eastern Europe. An unpalatable choice certainly but millions of lives rested upon that choice and arguably, the entire free world as well.

But that is the question. Was the sacrifice of Eastern Europe certain and inevitable? I’m not so sure. The war was started over Poland and while Poles and Czechs and the rest were better off than under the nazis, they certainly were not liberated. Delusions over the nature of Stalin’s regime as well as direct communist influence seem to have played a role. We were ready to take massive losses for “liberating” an already neutralized Japan but not to guarantee a free Europe.

No, the sacrifice of Eastern Europe was not certain and inevitable. It was a military choice. What was certain and inevitable was that if we invaded through the Balkans, a consequence of the allies attacking from the east and preempting the Soviet attack would necessarily involve many more allied deaths, as that strategy would have allowed Hitler to concentrate all of his forces on his eastern front.

Logic and long established military strategy also support the view that Hitler would more surely and more quickly be defeated, if he was forced to split his forces to defend against attacks from both the west and east. And that, that strategy would also lessen Allied deaths in fighting what amounted to a weakened western front.

It strains credulity to imagine that there were any real delusions over the nature of Stalin’s regime. After all, the brutal Soviet regime had been active from prior to 1917 and had many western observers, not all of whom were sympathetic.

Given what we now know, direct communist influence to some extent seems almost certain. It may well have led to an inordinate importance by FDR upon lend-lease having the highest priority but that Russia acting as an effective counterweight to Germany was a great advantage to the Allies is beyond dispute.

Hitting Hitler on two fronts and forcing him to split his forces is arguably what won the war.

A Balkan campaign could have been a viable alternative to the Italian campaign, but in no way could it have been a substitute for OVERLORD.

The Western Allies suffered high causalities in Italy against relatively few German divisions, for questionable strategic returns.

I don’t see how a Balkan campaign could have been a viable alternative to the Italian campaign. A Balkan campaign would have extended out of the Italian campaign. The allies couldn’t attack Germany directly from Italy as the alps stood in that path. Churchill favored swinging east out of the north of Italy and then up into the Balkans. Churchill for all his talents and importance was not a military strategist. An attack into Germany by way of the Balkans would have meant either preempting the Soviets or combining our attack from the east. In addition, timing would have been an issue in coordination. And, neither side would have felt comfortable having the other on its flank.

If memory serves me correctly, I believe one of the arguments in favor of a landing in Greece and up through Yugoslavia to attack Axis central Europe was that there would be less resistance to the offensive than the narrow Italian Front, and a rapid advance due to the fact that Partisans controlled large areas of Yugoslavia.

From Northern Yugoslavia, Allied forces could have either proceeded to the Reich, cut off the Germans in Italy, or attacked the rear of the Eastern Front.

Bulgaria, Rumania and Hungary probably would have capitulated rapidly, as Italy did once the first Allied boot stepped on the Italian mainland.

A map of the situation in Sept.43

upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/26/Kapitulacija_Italije_i_ustanak_u_okupiranoj_Jugoslaviji_1943.png

Sorry about the previous bad link

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Kapitulacija_Italije_i_ustanak_u_okupiranoj_Jugoslaviji_1943.png

This link is a pain in the neck. I hope that does it.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Kapitulacija_Italije_i_ustanak_u_okupiranoj_Jugoslaviji_1943.png

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Kapitulacija_Italije_i_ustanak_u_okupiranoj_Jugoslaviji_1943.png

I spent two years in Germany in the military. Its hard to believe you could fit the Whole country of Germany in the state of Texas. An they just about whipped half the world.

How about an amphibious landing in southern France, like along the Rivera? Did the Germans have fortifications along the Med. like they did along the English Channel? We already had troops in Italy. So we could have stock piled every thing along the African coast. I know logistics would have played a part, but at that time I think supply and troop ships going into the Med. would have been as quick as going to England. Plus we had air bases in Africa that could have flown air cover for the convoy’s.

People forget that we landed in the Riviera. The 7th Army (mostly US but some Brits and French (The 3rd Inf Div being the lead) Operation Dragon was conducted in August-September 1944 and was used to lever southern (Vichy – “unoccupied” France away from the Axis. This move gave us the port facilities of the Med – where Germany was powerless by 1944.

Italy was an important invasion, but no one understood how difficult the campaign would be. The Germans defended it like it was their own territory. The largest problem with Italy was its marginal attachment to the European Continent. The Alps and Switzerland made it largely an island. It eventually became a major logistical center, and served to command the Mediterranean.

For whatever reason the Brits were obsessed with the Greeks. I figure it was Churchill’s classical sense, but I really think that it was critical to their supply path to the middle east, where they found all of that oil that now hovers over the world’s head like the Sword of Damocles.

Militarily I don’t see much good an invasion from the Balkans would be, except having occupation forces there to peal away any potential Soviet gains in South Eastern Europe, and the Black Sea… (old traditional European worries.)

The primary and most useful invasion point was always France, across the English Channel, through the plains and valleys of the Lowlands, across the Rhine and into Germany.

The political reasons for how fast and how efficiently we made that fight will be studied for many more years beyond my meager digging.

Why did Bradley get waived off at Falaise (Patton’s 3rd Army was starved for fuel and ammunition just before he could cut north and cut their entire army off.)?

Why did Bradley miss the Ardennes Offensive in December 1944 when his intelligence was screaming at him that the Germans were building serious offensive resources and had attacked through the Ardennes several times over the last century?

Why, when Patton once again had the means to cut off an entire German Army group fast, with minimal casualties, and trap it did Eisenhower and Bradley order a brutal methodical personnel burning broad front advance to collapse the Bulge?

Those, again are choices that politicians and generals take. We know some things, and others we will remain in the dark for a while on. (Supposedly a major Archive declassification is supposed to happen beginning in a few years…)

Some of what we will see is probably going to be disheartening. Some of it will be illuminating and interesting. History is messy that way.

r/TMF

Ah, yes, this is the comment I was looking for. OC’s post is indeed one of her best and illuminating in every respect but it does not address the monumental disparity in casualties (although quite a few of these could be attributed to Stalin’s carelessness, sadism and many military mistakes as well as the willingness to spill Soviet blood by commanders like Zhukov) and the number of Germans killed between the USSR and the United States.

The $ and material (not to say all of the intelligence) sent to the Soviet Union and the decision to allocate resources to the Eastern Front rather than the Japanese theater facilitated Victory over Germany and the Axis generally at an almost incalculably lesser cost in American blood and treasure than would have been the case with a different policy.

The strategic, operational and geographic points adduced by Geoffrey and TMF are interesting and compelling.

Readers, I append here a response I made to GB over at LibertyUnyielding. It addresses some of the points you have raised here, which, as always, are intelligent and well expressed. (The New York Times should have such readers!). More later; today is not a good day for typing.

GB, you raise a point about Allied casualties that would be common among WWII history buffs. Over at the home blog, jgets has made the point that it was essential to open a front against Germany in the West.

On both points, it’s hard to say that they were what carried the day regarding OVERLORD. I don’t have time to outline the recent findings of M. Stanton Evans about FDR’s physical and mental condition in the last few years of his life, but it appears that FDR was even sicker and than we knew, and largely/often incompetent. A link to Evans’s 2012 book with Herbert Romerstein is at the end of this post.

After you read Evans and West on FDR’s condition and the course of decision-making in 1943-45 in Washington, the image of FDR as aware, competent, and shrewd is impossible to maintain. Based on the things he said about Stalin, FDR himself was either living under the illusion of a complacent, arrogant person whose contact with reality was compromised — an illusion carefully tended by his Soviet-agent advisors — or was a Soviet agent. I incline to the former explanation.

The totality of what we now know — and there may be more to come — suggests that FDR was not making decisions based on the likelihood of Allied casualties. He showed no solicitude for US troops fighting in the Pacific in 1942-43, certainly. And, as West outlines toward the end of her book, he made no real effort to recover US troops who were “liberated” by the Soviets from German POW camps in 1945, only to be shipped off to the Gulag. Some 15-20,000 of them were never recovered; the reports of third parties indicated that some were still alive and slogging away in the Gulag years later. (Boris Yeltsin apologized for this in a meeting with Bush 41, but, as West recounts, H.W. Bush actually shut Yeltsin’s apology down in front of the microphone and the press. Even a Republican president didn’t want this dirty linen from FDR’s final months aired in public.)

Churchill wanted to fight Hitler in Eastern Europe precisely because doing so would put the Western Allies’ armies in Eastern Europe and block Stalin. (Besides the Iron Curtain in northeastern Europe, Stalin’s moves on Greece, Turkey, and Iran from 1944 to 1947 vindicated Churchill’s concern about his intentions, and ended up prompting the Truman Doctrine.)

As far as I have ever known, there wasn’t a fully developed plan for a Western pincer to go along with the “Balkans strategy.” But Churchill acknowledges in his memoirs of the war that such a pincer would have been needed. Alternative concepts included landing troops in Vichy France to link up with troops driving north in Italy and approach Germany from west of the Alps. It was assumed that the French would rise up and fight if given the chance, and would be able to add to the strength of an Allied Western force within a matter of weeks.

Splitting German forces in the West and the East was important, and the point is not that it wouldn’t have been required in order to end the war in the quickest way possible (assuming it was to be ended through combat, that is. West outlines in excruciating detail the multiple realistic opportunities FDR had to accept a German surrender and get rid of Hitler).

The point is that Stalin’s plan, which is the one FDR adopted, forced Germany to pull more forces out of the East than any other plan would have, AND it left the Eastern front solely in Stalin’s hands. Both of those features were essential to Stalin — but were not so to FDR or Churchill, if their national interests, objectively considered, were the main factors in making the decision about strategy.

Churchill quite obviously was taking his national interests into account. He saw Stalin clearly, and he didn’t want Stalin to take over as a vicious, bloodthirsty hegemon over Eastern Europe, perpetually threatening Western Europe and the Mediterranean — along, potentially, with threatening South and Southwest Asia.

FDR doesn’t appear to have seen any of this. The emerging picture is of a sick, barely functioning president whose instincts were all political anyway, in the sense of domestic and personal-persuasion politics. There is no record of FDR as a strategic thinker or a man who cared about or understood history, geopolitics, or the philosophy of international relations. There is real reason to suspect that FDR came down on the side of OVERLORD solely because his trusted advisors, with their extensive penetration by the Soviet Union, said he should.

Anyway, big questions. I suspect that 50 years from now, when the people who actually shed the blood are all gone, historians will begin taking it as a given that the Soviet-penetrated FDR administration made most or even all of its key wartime decisions based on influence from Stalin. Our sense of why that matters will have changed by then as well.

Perhaps the extent of FDR’s incapacity in the last years of the war has not been widely known until relatively recently but his complaisance in respect of the USSR and Communism and his (relative) hostility or at least skepticism toward the British Empire (though certainly not England itself in this period) have been widely written about and generally recognized by almost anyone who took even minimal steps to learn about these matters. His concern for American lives may not have been decisive or even important in his decision making but it seems to remain the case that many hundreds of thousands of these were spared by a strategy that resulted in the Soviets killing millions of capable German soldiers and destroying and capturing large amount of German materiel.

Thanks, cavalier, it’s been a lively discussion. In hindsight, it may be an open question how many lives were spared by the choices we made. Other comments here have alluded briefly to how the Soviets fought, as a possible factor in their enormous casualties. Could we have fought the same Wermacht forces on the same territory without taking the same casualties? We don’t know. I wouldn’t automatically answer in the negative.

One thing we do know is that FDR’s record, overall, was not one of making strategic decisions with the end in view of sparing our troops’ lives.

I would have invaded Southern France, long before the Normandy Invasion, and would have made a right hand turn going east, north of the Alps, thous cutting off all the German Army’s to the south. There were a lot more likely to surrender to the Western Allies than to the Russians. Thus I think the war would have been over a whole lot quicker. Then if I had to, I would have invaded Normandy. I don’t have a bunch of WW2 maps in front of me, but I don’t believe that Southern France was as fortified as the Northern Part. Thus if most of the German Armies were occupied in Southern France, the Normandy Invasion would have been less costly.

Oh, of course OC. Indeed I refer to Stalin’s and the general Soviet profligacy with the lives of Soviet soldiers. Additionally a different strategy would not have eliminated the entirety of the Soviet contribution to defeating the German or placed the entire or even principal burden of doing so on the Western Allies (mostly, of course, on the U.S.). Still, accepting even a somewhat meaningfully increased part of that burden on the latter and assuming a much greater consideration for allied lives, assuming an increase in allied KIAs of several hundred thousand (2, 3, 4, 5?) does not seem a huge stretch. And while this would have been a very small fraction of Soviet casualties (too lazy to look it up now but I’m reasonably sure they sustained comparable numbers in individual weeks and certainly in many individual months on the Easter Front) it would still have been a very painful increase for the Allies.

Still, the point that this was not crucial to the strategy is well taken.

I’m less concerned with FDR’s motivations and more concerned as to whether, objectively considered, Churchill’s desire to attack through the Balkans so as to preempt the Soviets moving into Eastern Europe was a viable strategy in defeating Hitler. Certainly it would have stopped the Soviets from absorbing Eastern Europe, I’m not contending otherwise. Clearly, Churchill was thinking long term, as once America entered the war, he knew Hitler’s defeat was now just a matter of time. Regarding Germany however, I remain unconvinced that the Balkans offered a viable strategy.

There wasn’t a fully developed plan for a Western pincer to go along with the “Balkans strategy” because the possibility to do so didn’t exist. The ‘alternative concepts’ of landing troops in Vichy France to link up with troops driving north out of Italy and approaching Germany from west of the Alps fails to account for the German troops in France that would have stopped an Allied advance that necessarily lacked ‘push’. Hitler could still have concentrated the bulk of his forces in the east.

The French resistance had small arms and explosives, not tanks and air support. An Allied advance into France, to be viable would have had to have had all that a real army requires, including logistical support. The French guerrilla resistance would have added little strength to an Allied Western force.

It matters less whether FDR realized this, though I think it certain that he was advised of these realities and, not just by covert soviet agents. What matters from my point of view is what the actual military conditions consisted of…

I will say that the more I learn of FDR, the less impressed I am. Oliver Wendell Holmes, who met Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933 said of FDR that he had a ”second-class intellect, but a first-class temperament!”

Actually, GB, there wasn’t a fleshed-out plan to move northward through southern France because there wasn’t a fleshed-out plan to move northward through southern France.

It was no more impossible to do that than to invade Normandy. (As Mighty points out, we did invade France from the Med later in 1944, in Operation DRAGON. It wasn’t our primary thrust, however.) The only reason there was a fleshed-out plan to invade in the north is that that’s where we decided to invade. We were going to invade into German-held territory with either option.

The more we know, the more it appears that FDR was not in any condition to have motivations for choosing the northern invasion option. I do not think that his reasoning was based on military advice, which would have found challenges and benefits in both options. From a military perspective, we were going to take heavy casualties regardless of what we did, but either option for the main thrust — a Balkans entry or northern France — was feasible. The Balkans option, with a western front opened through southern and eastern France, could probably have been executed earlier than June 1944, before Stalin had pounded westward across so much of Eastern Europe.

The question is what the tiebreaker was. We have to remember that, especially in the years 1943-45, FDR did not get unfiltered military advice. That wasn’t how his White House worked. See again Evans and West. The image of FDR making decisions based on maps and talking generals in a “situation room” would be a false one. Churchill worked that way; FDR did not. The picture emerging from the recent scholarship on his wartime decisionmaking is of a president basically talking to Harry Hopkins, in the 4-hour window each day when Oval Office business was done, and receiving advice funneled through him. Hopkins was clearly not an unbiased filter. His connections with proven Soviet agents were significant, and he did too many things on behalf of Stalin — and against US interests — to make it reasonable to suppose that his advice on war strategy had an unbiased military quality.

“there wasn’t a fleshed-out plan to move northward through southern France because there wasn’t a fleshed-out plan to move northward through southern France.”

That’s circular logic JE.

“It was no more impossible to do that than to invade Normandy. …The only reason there was a fleshed-out plan to invade in the north is that that’s where we decided to invade. We were going to invade into German-held territory with either option.”

Of course it was just as possible to invade through the Balkans as through Normandy. I’ve never claimed otherwise. I am arguing that it was manifestly an inferior strategy, for the reasons stated. Whatever FDR’s rationale or influences, IMO he made the right military decision.

I’m sorry and with all due respect for your greater military expertise, the immediate military issue wasn’t whether we were going to experience heavy casualties, which was certain but rather which strategy led to the quickest and most sure ending of German resistance.

Militarily, forcing an enemy to split his forces is almost always the superior strategy and certainly was in this case. My position is that the Allies could not mount a sufficient two front attack without the Soviets.

However much FDR may have been influenced by Soviet agents changes that calculus not a bit.

No, GB, my logic is not circular. I’m demonstrating that it IS circular to argue that not having a fully-developed plan for opening a second front from southern France is a reason for not choosing that option.

We didn’t have a fully developed plan for opening the second front from northern France until … we had one. It is invalid to say that we couldn’t have developed a full plan for driving northward from southern France, as the principal supporting effort. Of course we could have.

My point, again, is not that we didn’t need to split Germany’s forces. It is that a two-pronged approach through the Balkans and southern France was feasible. German forces would have been split by that option as well as by OVERLORD.

I think your argument is that the northern-France approach was still preferable. There are points in favor of that argument, but they are not overwhelming or decisive in a military sense. There are points in favor of a two-pronged southern approach as well, such as that, had we put greater effort into Italy, the Italian peninsula could have served as a hub for operations in both the East and the West, and would have allowed us to bombard Germany more effectively from two axes — West and South — rather than just one (West).

OVERLORD was not the only feasible option, nor was it by far the best in a military sense. In some ways it was clearly the simplest, but in one key way it was the most difficult, in that it entailed landing into the greatest German strength.

In any case, once OVERLORD was decided on, it cannot be said that any other effort — especially in Italy — received all the resources it could have. We don’t know how quickly the Germans could have been driven north through Italy if we had not been positioning resources for OVERLORD. The only way to properly evaluate alternatives is to wipe the slate clean and ask what we would have done differently if we had committed to the two-pronged southern strategy, rather than constraining our thinking with decisions that were made because we didn’t.

The simplicity of OVERLORD, as compared to the less-simple southern strategy, is a good reason why the generals didn’t resist the northern plan, at least not with vigor (some of them did disagree with it). But to insist that geographic simplicity was the decisive factor in choosing the course is to deal out of the picture political considerations, which in fact are always paramount in war.

It is also to ignore things we are learning about FDR’s relations with his top military advisors. As early as July 1941, Harry Hopkins made this note to himself on a presidential cable (West, p. 184):

“Hopkins jotted down … the following: that after he ‘spent the afternoon with Stimson and Marshall’ — the secretary of war and the army chief of staff — ‘Stimson is obviously unhappy because he is not consulted about the strategy of the war, and I think he feels I could be more helpful in relating him and Marshall to the President.'”

Evidence does not suggest that purely military advice found better access to FDR in the next four years. We need not be conspiracy-minded to recognize that our national view of WWII as a conflict of cleanly “military” decisions and actions — i.e., as opposed to Korea and Vietnam, for example — is not valid in the comprehensive sense we have long assumed.

This is one of Diana West’s opening points: that our concept of WWII as the “good war” must suffer from these revelations about presidential decision-making. Within theaters and campaigns there was great scope for military brilliance, but the major decisions on priorities — Europe first, starve the Pacific; land in Normandy and short the Italian campaign to prepare for it; leave Eastern Europe entirely to Stalin — were made for reasons other than military necessity. In any war, such decisions would be made primarily for political reasons. What West has done is shine a light on what the political reasons were.

I meant to list as one of the major decisions on priorities FDR’s embrace of the “unconditional surrender” requirement for Germany, which was paired with his refusal to even respond to overtures from high-ranking Germans for a negotiated surrender. Such a choice would in any war be a purely political decision, entailing a calculus about the geopolitical conditions post-bellum.

It is not clear that FDR had an articulated reason for insisting on unconditional surrender. But it was certainly what Stalin wanted.

First of all, I’ve never argued that FDR wasn’t inordinately influenced by those sympathetic to Soviet goals. He may well have but that is not the basis for my disagreement and entirely irrelevant to my argument. Within the context of my objections, I don’t care why he made the right decision.

My point is that regardless of his reasons, he made the decision that ensured the quickest, most certain defeat of Germany and the least amount of allied deaths.

That Churchill was right that the resultant consequence of the allies attack from the West was the sacrifice of Eastern Europe to the Soviets, doesn’t change the points in favor of the allies attacking from the West.

The statement, “there wasn’t a fleshed-out plan to move northward through southern France because there wasn’t a fleshed-out plan to move northward through southern France.” absolutely is circular reasoning J.E. and long established rules of logic proclaim it to be.

” It is invalid to say that we couldn’t have developed a full plan for driving northward from southern France, as the principal supporting effort. “

We could have developed a plan but it would have been a flawed plan because such a plan’s strategic premise would have been that, splitting our forces and essentially telling the soviets to stay out of the fight was equally as militarily sound as forcing Hitler to split his forces while forcing him to face both allied forces and soviet forces.

“the Italian peninsula could have served as a hub for operations in both the East and the West, and would have allowed us to bombard Germany more effectively from two axes — West and South — rather than just one (West).”

Yes it could have served as a hub, that is not in dispute. But it is highly questionable that we could have bombarded Germany more effectively from Italy than from England. As Italy lacked the logistical resources that England offered. But even had we overcome those obstacles, that wouldn’t have changed the dynamic that, avoiding the splitting of one’s forces, while forcing your enemy to split his forces and force him to face a larger opposing force is a demonstrably superior strategy.

Thus it doesn’t matter that we “don’t know how quickly the Germans could have been driven north through Italy if we had not been positioning resources for OVERLORD” because regardless of how much resources we devoted to Allied forces in Italy, the negatives of invading through the Balkans remain.